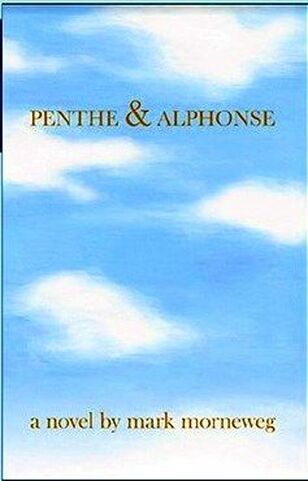

Literary style and form play important supporting roles almost as captivatingly heroic as those of the title characters in Mark Morneweg's highly-innovative novel: Penthe & Alphonse. A reader casually thumbing through the book's pages might do a double-take over the word "novel" on the front cover and wonder if it should be poems instead. Yet a second quick run through the book's 99 pages would reveal it is in fact comprised of 135 brief chapters anywhere from two single lines to three or four pages long. Having explored fusions of poetry and prose in works of my own with varying levels of success, I wondered how well Morneweg had met this challenge he issued to himself. Once I began reading in earnest, the chapters seemed to alternate like sequences in a film. They moved back and forth between flickering flashes of moments and extended scenes from the characters' private lives and America's public tragedy, also known as the Civil War. It soon became apparent the author has struck a masterful balance of historical detail, lyrical rhythm, and finely-nuanced emotional intensity. The book begins with Alphonse's older sisters looking from a window down on him and Penthe, two former childhood playmates now entering adulthood, in a New Orleans courtyard reading poetry by Francois Villon. The delicate intimacy between them is apparent and alluring. But because he is categorized racially as white and she, in the language of 1800s American south, as a biracial "octoroon" (meaning "three quarters French and one black") their intense intimacy is also dangerous. In addition, despite racial categorizations, they are second cousins. The kind of relationship Penthe and Alphonse had during childhood was not uncommon for the time, but most children were expected to "grow out of it" as they matured and retreat to their respective black and white demographic niches. Alphonse's and Pense's relationship, however, continues to develop through a series of circumstances along a more sensuous, humane, and uncompromising trajectory.

|

| | |

Racism directed against Penthe is something Alphonse makes clear he will not tolerate. When another man calls her "a part-nigger whore," he challenges him to a dual and manages to shoot him without killing him. At the same time, he suffers through moral ambivalence when it comes to fighting in the Civil War, demonstrating how complex the issues behind it truly were: "If the Yankees invade, I will fight them. I will fight, but I am not too thrilled. I will not be morbid in front of Penthe Anne." Such reasoning brings to mind the song by Sade: Love Is Stronger Than Pride.

From one minimalist chapter to the next, they love their way through war, two epidemics of Yellow Fever, race riots, the demands of grandchildren, and old age. Looking at a printed copy of Penthe & Alphonse, or even just the cover on a screen after reading the book, gives the feeling of staring at an optical illusion because Morneweg has managed, somehow, to deliver much more than what appearance promises. The range of time covered, scope and depth of emotions engaged, and intricacy of styles employed seem too much for the pages containing them.

What Geek Bookaholics Often Do

| | |

In the course of reading Penthe & Alphonse, I began to do what geek bookaholics often do when sensing that within their hands is not just a good book but a rare and beautiful kind of priceless mind. I began attempting to discern who the author's strongest literary influences had been. I could hear William Faulkner's spirit wandering between lines while meditating on the nature and traumas comprising the identity (or should we now say identities?) of the American south. But who were the others?

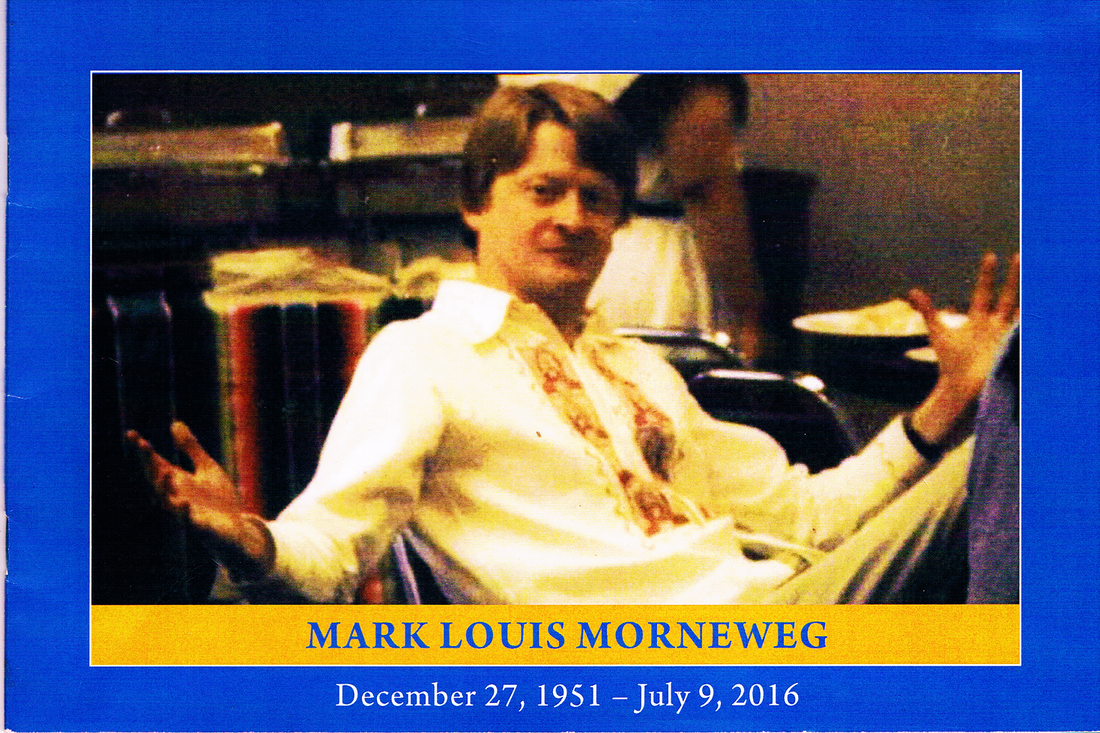

The answer came one day when I was discussing the title with a friend and she loaned me a copy of a booklet about one Mark Louis Morneweg published by El Portal Press. In it, he noted his passion for "Miss Emily [Dickinson]"along with deep appreciation for others who had also helped stir to action my own pen. Among them: Federico Garcia Lorca, Pablo Neruda, James Joyce, Shakespeare, Franz Kafka, Marcel Proust, and Albert Camus.

He shared these words in regard to his approach to writing fiction: "Unplanned adventures in literature. An idea pops into your head and you go from there. Nothing structured or laid out beforehand. Just one word comes and you have an entire chapter to write and that is great..." (The only time I had ever allowed myself that kind of compositional freedom was while writing Christmas When Music Saved the World, later titled Songs from the Black Skylark zPed Music Player.)

Maybe even more importantly for the purposes of this essay, he told us this: "...I am a prose stylist with some amazingly short chapters. Some chapters that are poems. Prose poems." And added: "Penthe is about taking risks. Artistic risks. Passion..." The risk was one that paid off extremely well because ultimately Penthe & Alphonse succeeds as both an epic poem and an amazing novel.

Moreover, in addition to taking risks, it is also about what Lady Gaga refers to as the right to curate one's life as one sees fit. Along those same lines, Morneweg chose not to douse the flames of his startling creative literary inventiveness. He chose instead to feed the fire with boldness sufficient enough to increase its light and heat so others could gather around and savor the prize of unexpected beauty.

| | |

By Aberjhani

Harlem Renaissance Centennial

Co-author of Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance

Author of Greeting Flannery O'Connor at the Back Door of My Mind

| | |

Archives

November 2023

June 2023

February 2023

December 2022

June 2022

February 2022

November 2021

September 2021

April 2021

March 2021

December 2019

November 2019

June 2019

May 2019

March 2019

January 2019

October 2017

July 2017

August 2012

Categories

All

1950s

1960s

2022 Russia Ukraine War

20th Century Authors

21st Century Artists

21st Century Authors

21st Century Poets

Aberjhani

Aberjhani Observance Of National Poetry Month

Aberjhani On Aurie Cole

Aberjhani On Brad Gooch

Aberjhani On Chinese Famine

Aberjhani On Dick Gregory

Aberjhani On Duncan McNaughton

Aberjhani On Eugene Talmadge

Aberjhani On Flannery O'Connor

Aberjhani On Immigration

Aberjhani On Jean-Paul Sartre

Aberjhani On Mao Zedong

Aberjhani On Mark Morneweg

Aberjhani On Maya Angelou

Aberjhani On Otis S. Johnson

Aberjhani On Paul Laurence Dunbar

Aberjhani On PT Armstrong

Aberjhani On Russia Ukraine Was

Aberjhani On Savannah Georgia

Aberjhani On Savannah-Georgia

Aberjhani On Yang Jisheng

Adapting Books For Film

Africa

African American Authors

African-American Authors

African-American Comics

African American History Month

African American Men

African-American Men

African Americans

African Americans Abroad

African Americans In Japan

African Americans Living Outside America

African American Writers In Savannah GA

African Diaspora

African Engineers

African Writers

AI Literary Chat Salon

Alice Walker

Amanda Gorman

American Artists

American Authors

American Civil War

American PEN Video

Andrew Davidson

Angel Art

Angel Lore

Angel Meme

Angel Of War And The Year 2022

Angelology

Annie Cohen-Solal

Antiracism

Archangel Michael

Art By Aberjhani

Art By Christia Cummings-Slack

Artist-Author Aberjhani

Artist James Russell May

Artist Marcus Kenney

Asian Authors

Audio Podcast

Aurie Cole

Author Brad Gooch

Author Connie Zweig

Author Franklin D. Lewis

Author Interview

Author Mark Morneweg

Author Poet Aberjhani Official Site

Author-Poet Aberjhani - Official Site

Authors

Authors From Savannah Georgia

Ava DuVernay

Benjamin Hollander

Benjamin Van Clark Neighborhood

Ben Okri

Ben Okri Videos

Best Interviews Of 2023

Bill Berkson

Biography

Biracial Relationships

Biracial Women

Black History Month

Black Men Who Write

Black Movie Directors

Black Women Authors

Blogs By Aberjhani

Booker Prize For Literature

Booker Prize Winners

Book Industry

Book Publishing

Book Reviews

Book Reviews By Aberjhani

Books

Books About Rumi

Books About Savannah-Georgia

Books About Sufism

Books And Authors

Books By Aurie Cole

Books By Darrell Gartrell

Books By Flannery O'Connor

Books By Patricia Ann West

Books By PT Armstrong

Books By Robert T.S. Mickles Sr.

Books By Rotimi Ogunjobi

Books On Flannery O'Connor

Brad Gooch

Brad Gooch Audio Podcast

Brunswick Georgia

Canadian Authors

Canadian Novelists

Carlos Ruiz Zafon

Caste The Origins Of Our Discontents

Celebrity Authors

Children's Literature

Chinese Authors

Chinese History

Christia Cummings-Slack

Christina Cummings-Slack

Christine Cummings

Classic Authors

Connie Zweig

Contemporary African Literature

Contemporary African Writers

Contemporary Artists

Contemporary Authors

Contemporary Canadian Authors

Contemporary Literature

Contemporary Southern Literature

Cormac Mccarthy

Cornel West

Creative Nonfiction

Creative Thinkers

Cultural Demographics

Cultural Heritage

David Gordon Green

Dick Gregory Videos

Digital Publishing

Director Regina King

Director Steve McQueen

Doctorate In Literature

Dreams Of The Immortal City Savannah Book By Aberjhani

Duncan McNaughton

Ebooks

Education

El Portal Press

English As A Second Language

English Learning Students

Essay On 21 Years Of Wisdom

Essays By Aberjhani

Essays On Ben Okri

Essays On Duncan McNaughton

Essays On Flannery O'Connor

Essays On Immigration

Eugene Talmadge

Eugene Talmadge Memorial Bridge

Evolving Cultures

Existential Creativity

Existentialism

Fall Of The Rebel Angels

Famous Women Artists

Fiction

Filming Movies In Savannah-Georgia

Flannery O'Connor

French Authors

French Literature

Genre Bending Literature

Genre-bending Literature

Global Community

Grandmothers

Great Sufi Poets

Greeting Flannery O'Connor At The Back Door Of Mind Book By Aberjhani

Gullah Geechee Culture

Gustave Flaubert

Halloween's End

Hector France

Historical Fiction

Historical Poetry

History

History Of Civil Rights Movement

History Of Famines

History Of Literature

History Of Racism

Human Cannibalism

Iconic Authors

Immigrant Experience

Immigration Policies

Influential Authors

International Authors

International Poets

Interracial Relationships

Interview

Isabel Wilkerson

Jalal Al-Din Mohammad Balkhi

Jalal Al Din Mohammad Rumi

Jalal Al-Din Mohammad Rumi

James Joyce

Jean Genet

Jean-Paul Sartre

Jelaluddin Rumi

Jim Crow Racism

Lady Gaga

Latino Ficiton

Leadership Philosophy

Leadership Theory

Life And Legacy Of Dick Gregory

Life And Legacy Of Flannery O'Connor

Lillian Gregory

Literary Biographies

Literary Community

Literary Criticism

Literary Essays

Literary Friendships

Literary History

Literary Honors

Literary Influencers

Literary Influences

Literary Legacies Of The South

Literary Prizes

Literary Traditions

Literary Translations

Literature Of Immigration

Luca Giordano

Memoir

Memoir By Darrell Gartrell

Michal Majernik

Movie Sets

Mythology

National Poetry Month

Naturalism Fiction

New Orleans

Nicanor Parra

Nigerian Authors

Nigerian Literature

Nigger By Dick Gregory

Nobel Laureates

Nonfiction

Novels

Official Site For Author Poet Aberjhani

Official Site For Author-Poet Aberjhani

Official Website Of Author Poet Aberjhani

Official Website Of Author-Poet Aberjhani

Oklahoma City

Oprah Winfrey

Patricia Ann West

PEN America

PEN International

Philosophy

Podcast On Literature

Poems About Savannah-Georgia

Poems By Patricia Ann West

Poetry

Poetry By Aurie Cole

Poetry By Duncan McNaughton

Poets Against War

Poets From

Poets From Afghanistan

Poets From Boston

Poets From Savannah Georgia

Poets From Savannah-Georgia

Poets On War

Political Activism

Political Biographies

Political Strategies

Political Theories

Postered Poetics Art By Aberjhani

Predatory Gentrification

Preventing Erasures Of History

Prose And Poetry

Prose Poem

Public Intellectuals

Public School System

Publishers

Publishing

Publishing Options

Putin Attacks Ukraine

Q&A With Author

QOTD Quote Of The Day

Quentin Tarantino

Quotations

Quotes By Dick Gregory

Quotes By Flannery O'Connor

Quotes By Mark Morneweg

Race In America

Race In Japan

Racism In Georgia

Racism In Savannah

Racism In The United States

Reiki Master

Richard Wright

Rotimi Ogunjobi

Rumi's Birthday

Russian Invasion Of Ukraine

Russia Ukraine Conflict 2022

Russia Ukraine Video

Russia Ukraine War

Salman Rushdie

Sandfly In Savannah Georgia

San Francisco Poets

Savannah College Of Art And Design Graduates

Savannah Georgia

Savannah-Georgia

Savannah River

Savannah State University

SCAD Graduates

Singer Sade

Social Activism

Social Realism

Somewhere In The Stream By Duncan McNaughton

South Carolina

Southern Legacies

Spike Lee

Spiritual Counseling

Spirituality

Starvation

Still Water Words

Sufi Literature

Talks Between My Pen And Muse

Teachable Take-Aways

Text And Meaning Series By Aberjhani

The American Poet Who Went Home Again

The Angel's Game

The Famished Road

The Gargoyle By Andrew Davidson

The River Of Winged Dreams

The Word "Nigger"

Toni Morrison

Transgression Fiction

Transgression Literature

Transgressive Literature

Tribute To Dick Gregory

Ukraine Russia Crisis 2022

Video

Video Podcast

Video Poem

Videos About Rumi

Videos On Literature

Wakanda Forever

War And Peace

William Anderson

Wisdom21

Women Artists

Women Authors

Women Poets

Women's Voices

World Community

World History

World Poetry Day

Writers And Writing

Xenophobia

Yang Jisheng

Year 2022 In Review

Yoko Ono

YouTube Videos

RSS Feed

RSS Feed