|

This Q&A with prolific author Rotimi Ogunjobi is the second part of a special 2-part feature on the literary titan. The first part, titled Versatility and Vision… provides an in-depth look into the writer’s background. It was published in the AI Literary Chat Salon here at Bright Skylark and you can check it out it out by clicking here. The interview with Ogunjobi begins now: AI Literary Chat Contributor: You have been actively involved in various forms of writing, from novels to plays and poetry. How do you perceive the role of literature in addressing the pressing political and social issues of our time, particularly within the context of Nigeria and the wider world? Rotimi Ogunjobi: As a Nigerian author, I view literature as a powerful tool for addressing pressing political and social issues both in Nigeria and on a global scale. Literature has the unique ability to engage readers on a deep and emotional level, allowing them to connect with complex issues in a way that is both thought-provoking and empathetic. In the context of Nigeria, a country with a rich and diverse cultural heritage, but also facing a myriad of challenges, literature plays a crucial role in several ways. Among other factors, it helps raise awareness concerning important issues, it promotes dialogues, documents history and supports cultural preservation all at the same time that it inspires change. AI LCC: And in what way would you say this is significant in the larger world community? RO: On a wider global scale, literature from Nigeria and other parts of Africa contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the continent's complexities. It challenges stereotypes and misconceptions and highlights the rich tapestry of African life, culture, and history. In essence, literature has the power to be a catalyst for change, a source of education and enlightenment, and a means of preserving culture and history. I believe it is my duty to continue using my craft to address pressing political and social issues, share the stories of my people, and contribute to a more informed, empathetic, and connected world. AI LCC: Your literary career has spanned several decades, and you’ve seen significant changes occur in the publishing industry. How have these changes influenced your approach to writing, publishing, and connecting with readers? RO: Traditional publishers in Nigeria focus mainly on educational content, primarily because the recreational reading culture is not quite encouraging. Even the small publishers of fiction books strive to get their products into the school reading lists just to be able to make a bit of profit... AI LCC: So how did the priorities of traditional publishers affect your choices and processes? RO: As most of my books have been self-published, some of the key ways which changes in the industry have shaped my literary journey involved such events as the development of technology and digital publishing, the global reach made possible by the internet, genre diversity, and social and political engagement. These have all had strong impacts on my literary processes. When it comes to genre diversity in particular, the evolving publishing industry has allowed me to explore various literary forms, from novels to plays, poetry, children's books, and folklore collections. This diversity not only keeps my writing fresh and exciting but also caters to different age groups and interests, making my works appealing to a broader range of readers. AI LCC: Translations of your works into multiple languages have undoubtedly broadened your readership. Could you tell something about how this multilingual approach contributes to cross-cultural understanding and the dissemination of African narratives? RO: Indeed, facilitating the translation of my works into multiple languages has been a deliberate and important part of my literary journey as a Nigerian author. I have been able to achieve this mainly through a revenue sharing translator community. This multilingual approach plays a significant role in fostering cross-cultural understanding and the dissemination of African narratives in several ways. Africa is a continent with incredible linguistic diversity, and each language represents a unique cultural perspective. By translating my works into multiple languages, I aim to break language barriers and make my stories accessible to a wider African audience. This helps in preserving and celebrating the richness of African cultures and languages. Translation also allows my stories to transcend geographical and linguistic boundaries, reaching a global audience that may not be proficient in the original language of the work. This, in turn, contributes to a more accurate and diverse representation of African voices in the global literary canon. In addition, translations help break down stereotypes, have significant educational value, and can serve as a kind of cultural diplomacy. All of these promote a more inclusive and interconnected global literary landscape, which is something I am committed to continuing. AI LCC: The different genres into which you’ve ventured include children's books and African folklore collections. How does your background in engineering inform your creative process when crafting stories for younger audiences? RO: …Engineering emphasizes precision and attention to detail. When writing children's books, I think I unconsciously apply this mindset to the structure of the story. I carefully plan the plot, pacing, and character development to ensure that the narrative flows smoothly and engages young readers effectively. It is [also] true that engineers are trained to solve complex problems systematically. This skill set is invaluable when creating stories that need to convey moral lessons or address important issues for children. I approach these challenges methodically, ensuring that the message is clear and relatable. It is also true that engineers are trained to consider cause-and-effect relationships and logical sequences. This skill helps me create coherent and engaging narratives in children's books. Young readers appreciate stories that make sense and follow a logical progression. Not that the foregoing define my writing though. The primary objectives of my children's books are either to teach a memorable moral lesson or to make the reader laugh. I feel great if the story does both. I love being able to engage young readers in a way that encourages their curiosity, problem-solving abilities, and critical thinking while immersing them in the rich world of storytelling. AI LCC: In your extensive body of work, you've authored plays and even produced documentary films based on your narratives. How do you believe the transition from written word to visual medium impacts the way your stories are received and understood by audiences? RO: It is my hope that the transition from the written word to the visual medium, such as producing documentary films based on my narratives, will have a significant impact on the way my stories are received and understood by audiences. It is an expensive medium which I confess I am not at all financially prepared to fully engage. Regardless, I think first of the expected result and believe that the means will show up somehow. It is all we can do as artists. Transition from written word offers unique and powerful ways to engage with the narratives and to enrich the audience's experience. The medium itself can enhance readers' connections to the story, broaden its reach, and provide a deeper understanding of the themes and cultures portrayed… A visual medium often involves collaboration with filmmakers, actors, and production teams. This interdisciplinary approach can bring fresh perspectives to the narrative, enriching it with new insights and creative interpretations. Films can reach a broader and more diverse audience than books alone. They are accessible to people of all ages and literacy levels. This accessibility ensures that the story's message and themes can be shared with a wider range of viewers, including those who may not be avid readers. Documentary films in particular can be valuable tools for preserving oral traditions. They allow for the recording and sharing of traditional stories, myths, and rituals, ensuring that they are not lost to time. However, it's important to note that the transition from written word to visual medium also comes with challenges, such as the need to condense complex narratives, make creative choices, and adapt the story for a different format. Balancing fidelity to the original work with the demands of visual storytelling requires careful considerations. AI LCC: You've authored fictional works with thought-provoking titles like The Dreamers, The Bata Dancer, and The Crooked Bullet. Could you shed light on the underlying themes and messages that you hope readers take away from these novels? RO: Much of what you need to know about my books, you will find in my literary autobiography, Gathering the Words, subtitled, why I wrote what I wrote. It tells the reader about the circumstances that gave birth to each story idea . It is my book of books. In any case I will briefly answer your question about those three books you have mentioned. The Dreamers was initially titled “A Conference in Ennui" when submitted to the BBC Book contest, from which it won a place on the long list. The novel was self-published as "Somber City," and later as The Dreamers. The story centers on the tumultuous experiences of various characters in Lagos, each facing their own trials during a challenging period of economic hardship. The main character, a young engineer, initially loses his job and naively expects a quick reemployment. The unforgiving environment of Lagos eventually leads him to a mental hospital. Another character, a man who has escaped the troubled and polluted Niger Delta, secures a low-paying job as a security guard but struggles to provide for his family when his wife gives birth to triplets. The novel also introduces a schizophrenic youth deported from America who adopts a disturbing life philosophy and plans a misguided act involving the Defense Headquarters building. This act ultimately lands him in a mental hospital. Lastly, there is a sociopathic policeman who derives pleasure from tormenting others but is eventually driven to madness by a voodoo curse. These are some of the dreamers that crossed the timeline of his life during this period of distress. The novel The Bata Dancer is about a distinctive drum and dance tradition originating from the Yoruba tribe in South West Nigeria. Over time, it has spread not only within West Africa but also to various parts of the world. The Bata Dancer was one of the most challenging stories for me to write. It required three years of extensive preparation before I could begin writing the book to authentically portray the world of Bata dance. My goal was to delve deep into the perspectives of both the drummers and the dancers, essentially immersing myself in the world of the Bata dancer. At its heart, the novel is a romance tale about a young man seeking to rebuild his life, his connection with a legendary dancer, and his journey to master the art of Bata dance. AI LCC: And what about your novel, The Crooked Bullet? RO: During my time living in London, England, my bus commute home would sometimes pass through Whitechapel. The area has a notorious history of crime, including its connection to the infamous Victorian murderer Jack the Ripper, and for being the residence of the famous Kray Twins, who were prominent figures in organized crime during the 1950s and 1960s. I have a deep appreciation for comedies, and one of my favorite comedy films is "The Black Bird," which features a detective named Sam Spade [who is] constantly caught up in comical situations. This film is a parody of an earlier work based on the novel The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett, published in 1930. In my story, The Crooked Bullet, based in East London, I explore a similarly quirky theme as seen in The Black Bird. However, the main difference lies in the protagonists. While Sam Spade is portrayed as an experienced detective, the hero of The Crooked Bullet is a bumbling amateur attempting to transition from a former career as a newspaper reporter to a new role as a private investigator. Adding to the comical intrigue, our hero also has an intriguing sideline as a disk jockey. AI LCC: As we conclude this interview, could share some thoughts on what you believe you have accomplished thus far as a writer, both artistically and in terms of contributing to humanity's understanding of complex issues? And what aspirations do you hold for your future literary contributions to society? RO: My journey as a Nigerian author is an ongoing exploration of the power of storytelling to inform, inspire, and create positive change. I am committed to continuing this journey, with the hope that my literary contributions will continue to resonate with readers and contribute to a more inclusive, empathetic, and enlightened world. I believe that, at this point, I have accomplished several things both artistically and in terms of contributing to humanity's understanding of complex issues. Artistically, I consider the diverse body of my work as an accomplishment for the contribution it represents as forms of cultural preservation, as an educational resource, and as tools important to cross-cultural understanding and social commentary. Insofar as contributions to humanity's understanding of complex issues are concerned, I have attempted to provide authentic and diverse representations of African voices and experiences. This is essential in challenging stereotypes and promoting a more accurate understanding of Africa and its people. My literature has acted as a bridge for cultural exchange, enabling readers from different backgrounds to engage with and learn from African narratives and traditions. I have also used my writings to raise awareness of social issues, both within Nigeria and on a broader global scale. It is my hope that my contributions have inspired others to explore their own creative potential and share their unique stories with the world. AI LCC: We at AI Literary Chat Salon are thankful to author Rotimi Ogunjobi for taking time to join us this special feature. To read our preliminary profile of the author, please click here. To explore more about contemporary and classic cultural arts happenings at the Salon, please check out the listings below and click to gain full reading access for free. By ChatGPT Op-Ed Contributor 4114 In editorial partnership with Aberjhani Special to Literary Chat Salon Launch 2023 DISCVOVER WHAT ALL THE TALK IS ABOUT INSIDE THE LITERARY CHAT

0 Comments

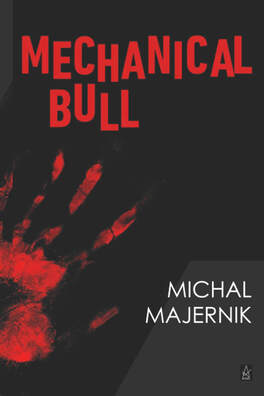

Fans of stylistically-rich literary fiction have only to read the first few pages of Michal Majernik’s novel, Mechanical Bull, to realize they have just discovered a rare kind of talent. It is one sharply aware of the soul-suffocating urban environments in which 21st century humans have encased themselves, and equally cognizant of the psychological dilemmas caused by their pursuits of illusory security and something resembling genuine love. The question after realizing the rarity of Majernik’s gifts (a relative newcomer to literary fiction, at least for this reader) becomes: what is he going to do with them for the rest of this book? And how might he utilize them in future works? For now, it’s worth noting that previous efforts as represented by his short story collection Alibist, and work as a journalist reporting on businesses in Canada, are put to advantageous use. Occasional typo malfunctions in the current work raise some concerns but, fortunately, do not diminish the strength of the story itself. Lava and Tears Mechanical Bull (Adelaide Books, 2021) is a novel driven by the mercurial force of its three main characters’ often unpredictable, and at times violent, personalities. Each stars in their own chapter. We first meet Berlin Fearne, an “energized and positive achiever” on her way to work in Hogtown (if you’re thinking Chicago, switch to Toronto). In her professional life, Berlin appears to be an ambitious exacting marketing executive who demands promptness and precision. By contrast, in her personal life, she is prone to compulsions and obsessions which lead her to casually commit theft while simultaneously purchasing expensive items which she neither can afford nor has any intention of keeping permanently. At home, Berlin and husband River Fearne argue over who is more to blame for their financial and marital woes. Is it her for being “miserable” and “shallow,” or him for being “the animal and the demon” loser who has not held a steady job in 10 years and does not know how to comfort her? In short, they routinely physically and verbally abuse each other to the point of accepting their lethally toxic relationship as love, like two volcanoes convulsively spewing lava and tears all over each other. It is clear the mania and desperation driving them can only lead to something horrible. What that horrible thing may or may not be, however, is less apparent. Should, for example, the reader interpret it as literal or metaphorical when the author writes, “Emptiness filled her. Coma took her”? Any doubt is erased 115 pages later. Style and Heartbreaking Substance Majernik’s style of literary construction fuses elements of different forms in lushly-layered passages of poetic prose with blade-sharp dialogue. Exchanges between characters run the gamut from unsparing intensely-heated tirades to soft menacing seductiveness. These are perhaps qualities of the raw naturalist and transgressive genres with which some readers will likely identify Mechanical Bull. While the author’s individual tweaks of the blended forms are effective for his creative purposes, and more than likely thrill any number of readers, it also possibly leaves those who prefer more linear plots and bluntly descriptive background stories feeling frustrated. At the same time, it has to be said that Majernik depicts his characters’ ever-evolving states of mind––whether driven by heartbreak and loneliness, or disappointments and delusion and drugs––with exceptional skill. So much so, in fact, that a reader can come close to empathizing with their twisted brands of logic. Introducing Clare MorganFollowing our introduction to Berlin, we meet Clare Morgan. She is a college student who engages in various kinds of sex for pleasure as well as for different profitable purposes (including obtaining well-written papers). She imagines making herself “available” to different young men in order to “save them from themselves.” Among Clare’s multiple multicultural lovers is her former internship supervisor, and Berlin’s husband, River Fearne. On the surface, Clare appears to be comfortable with her recreational dalliances and for-profit hook-ups. Beneath that surface, she intentionally inflicts pain upon herself for her transgressions and prays at length: “…heavenly Father, that you Transform my unyielding Heart of Stone into merciful Heart of Flesh.” (p. 58) She invests faith in her “boundless love” for River to a degree that, as Beyonce once sang of such obsessiveness, is DANGEROUS. In a letter, she writes: “…My beautiful River, my Judas, my Patron Saint of Torments, I love You, and I will never permit you to abandon me… May I eat your wounds?” (p. 95-96) Witnessing the extreme back-and-forth of this schism between abandoned moral convictions in pursuits of success, and the physical punishing guilt that can follow, immediately brought to mind passages by James Joyce. And perhaps Flannery O’Connor’s Hazel Motes from Wise Blood. Annoyingly, I kept picturing Joyce at times grimacing, laughing nervously, or crying. O’Connor might have been secretly impressed and just as quietly alarmed by Clare’s use of self-harm as a path to divine grace or love. It is in Clare’s story that readers may experience the clearest sense of the author’s interest in how socioeconomic hierarchies make and break individual lives, and how those who maintain them spawn the darkness-versus-light narratives that dominate many people’s day-to-day existence. Majernik curve-balls his own narrative when sharing the views of one of Clare’s wealthier connections, Etienne Leclerq: “…Money made the poor believe that they were alive, they shopped and indulged in order to live… Power was the one true value in the world, an immovable object, the undefeated timeless effort, the stone that held the sword. Money owned the poor. Power owned the rich, and the rich didn’t mind” (p. 80). Should readers attribute such musings to Majernik’s stated fondness for classic authors like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Emile Zola? Or should they simply consider it a natural outcome of economic and racial inequities observed worldwide prior to the pandemic and suffered dramatically during it? The Philosophical Question The author on occasion has described himself as “an agent of the absurd” that rings with loud truth as readers get to know River Fearne a lot better in the third final section. A barrage of explosive and implosive occurrences bring his character and the novel as a whole into a greater focus. Exactly what role River might play in any final resolutions or conclusions is, at first, hard to anticipate because the nature of his character can be interpreted in different ways. He appears at times to be a transplanted victim of his society’s institutionalized bias and his wife’s neurotic ambitiousness. In his best moments, he comes across as a sentimental thug, reciting to anyone who stands still long enough to listen: “Did you know that all matter in the universe comes from collapsed stars? You and I are stardust.” This poetic scientific refrain was first popularized by the late astronomer Carl Sagan and seems River’s way of affirming he is as good as anyone else, despite any societal data or individual behaviors suggesting otherwise. In total contrast to the letter which his lover Clare wrote him earlier in the story, he types the following to his wife Berlin: “Your life is a monument to gamble, and I can no longer live life on a constant edge, in constant anxiety, in constant fear of losing everything… you always run into unsettled situations. A hard life with no resolution in sight” (pp. 121-122). At his worst, River numbs the pain of his anguished frustrations with an overload of drugs and alcohol. The resulting blurred lines between reality and hallucination lead inevitably to the death of an innocent at, of all things, a baseball game. The word ‘death’ instead of murder is used intentionally here because the philosophical question which follows it becomes similar to one posed by the predicament of Richard Wright’s Bigger Thomas in the novel Native Son. Is this death more the fault of the one who finds blood on his hands? Or that of the machinations of a society which, arguably, make such outcomes inevitable? The anticipated resolutions to all that has occurred before––or the “click” as termed by Majernik––does arrive. It comes in the form of a string of absurd, and even comical, events which function to both punish River for, and absolve him from, his transgressions. I will leave the details of these events for readers to discover on their own. Only a Single Glimpse Authors who have boldly ventured into the unconventional territories of transgressive and naturalist fiction include such contemporary notables as Megan Abbott, Bret Easton Ellis, and Chuck Palahniuk; plus, more classic talents like Williams S. Burroughs, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley, and the aforementioned Joyce. There is much in Majernik’s novel o suggest he might one day earn a solid place among them. What makes his bitches brew of a book called Mechanical Bull worth reading is how finely he renders his characters against a subdued background of conflicting societal demands. These demands routinely grind out barely-surviving metaphors of a humanity still blessed with tremendous opportunities for genuine fulfillment but too scarred by perpetual trauma to realize them. This is only a single glimpse, albeit through a mirror darkly, of our chaos-plagued world but one luminous and revealing nonetheless. READERS ARE INVITED TO POST ANY RELEVANT COMMENTS BELOW. Aberjhani |

Archives

November 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed